How the interaction between lysosomes and mitochondria limits growth of Salmonella in macrophages

Macrophages play a central role in our immune system. They trap invading pathogens in the body and digest them inside. However, some bacteria such as Salmonella or mycobacteria are able to resist the digestive tract of macrophages known as lysosomes and thus evade the attack of immune cells. Research from the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics in Freiburg reveals how different organelles of macrophages communicate with each other to activate particularly effective antibacterial defense mechanisms. Thus, the successful clearance of some types of bacteria depends on a signal transmitted by the phago-lysosomal system to another organelle system, the mitochondria. This hitherto unknown interaction of lysosomes and mitochondria within immune cells may offer new starting points to better control infectious diseases.

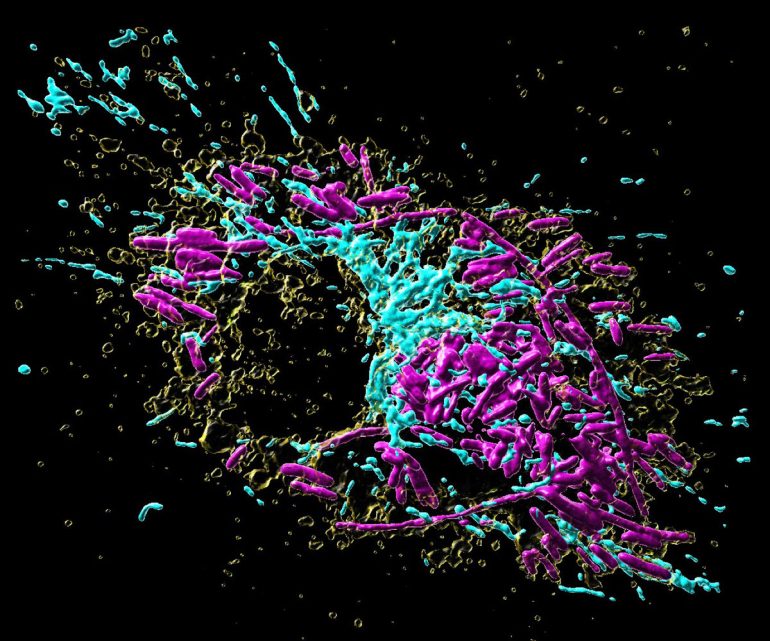

© MPI for Immunobiology and Epigenetics, AS Rambold

An infected primary macrophage containing the proliferation of Salmonella bacteria inside. Mitochondria are shown in blue, yellow: lysosomes, magenta: salmonella.

© MPI for Immunobiology and Epigenetics, AS Rambold

Macrophages are one of the most important defense cells of the innate immune system. They are found in nearly every tissue in our body and play an essential role in the health of our organs, as they continually remove dying cells and eliminate microbes that invade tissues. Macrophages are considered professional scavenger cells because they are particularly good at absorbing, destroying and thus destroying foreign material and pathogens.

However, some bacteria, such as Salmonella, have evolved strategies to evade digestion within macrophages, leading to severe inflammation such as typhoid infection. In their latest study, scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics in Freiburg describe how the interaction of two organelles, the lysosome and the mitochondria, inhibits the growth of these bacteria in macrophages.

signal from the cellular digestive system

Like most other cells, the inside of the macrophage is divided into several different compartments. These subunits of a cell, known as “organelles”, each perform specific functions, which are analogous to organ systems in humans, which perform specialized functions in the body. As scavenger cells, macrophages have a very specialized digestive organ, the phago-lysosome, in which microorganisms are usually broken down into pieces and thus inactivated. “It has long been known that the protein TFEB, in its function as a transcription factor, plays an important role in the control of the phago-lysosomal system. Recent findings have also shown that TFEB also plays a role in bacterial defense. important,” says the study’s leader, Angelica Rambold, of the Max Planck group.

She and her research team wanted to find out how TFEB mediates this antibacterial role in macrophages. They initially confirmed previous findings that a wide range of microbial, bacterial and inflammatory signals activate the proteins TFEB and the phago-lysosomal system. “It makes perfect sense that pathogenic and inflammatory signals activate TFEB. Lastly, after eating bacteria, macrophages require a more active digestive system. Interestingly, however, our experiments have identified another intracellular organelle system – showed a remarkable effect of TFEB activation on mitochondria. This was completely unexpected and new to us,” says Angelica Rambold.

Instructions to Mitochondria: Turn on Antimicrobial Quality

Mitochondria are often referred to as the “powerhouses of the cell”. Consisting of an inner and an outer membrane, these organs are the primary sites of cellular respiration, where energy is released for the cell from the nutrients supplied. In immune cells, however, mitochondria also serve as a source of antimicrobial metabolites.

Using a wide range of experimental techniques, such as metabolomics and various imaging techniques, the team was able to identify the precise signaling pathway that controls the interaction between lysosomes and mitochondria. “During the immune response, macrophages use an interesting inter-organic signaling cascade: the lysosome activates TFEB, which then migrates to the cell nucleus, where it regulates the transcription of a protein called IRG1. In turn , this protein is introduced into the mitochondria, where it serves as an essential enzyme for the production of the antimicrobial metabolite itaconate,” explains Angelica Rambold.

Using organelle communication to control bacterial infection

The researchers continued to investigate whether they could use this newly identified signaling pathway to control bacterial growth. “We suspected that activation of this signaling pathway could be used to inhibit certain bacteria, such as Salmonella,” says Angelica Rambold. “Salmonella can survive degradation by the phago-lysosomal system. They manage to grow inside macrophages, which can lead to the distribution of these bacteria to multiple organs in the infected body,” explains Alexander Westermann, associate partner of this study, who Helmholtz is a group leader and junior professor at HIRI. University of Würzburg. When the researchers activated TFEB in infected mouse macrophages, the TFEB-Irg1-itaconate signaling pathway inhibited the growth of Salmonella in the cells. These data indicate that the interaction of lysosomes and mitochondria constitutes an antibacterial defense mechanism designed to protect macrophages from being abused as sites of bacterial growth.

Given the increasing incidence of multi-resistant microbes, experts expect more than ten million deaths worldwide by 2050. It is therefore extremely important to find new strategies to combat bacterial infections that evade natural immune control. The TFEB-Irg1-itaconate signaling pathway or the pharmacological use of itaconate itself may be a promising approach to treat infections caused by itaconate-sensitive bacteria. According to the scientists in Freiburg and Würzburg, however, further investigation is needed to determine whether these new starting points can also be successfully used in humans.

AR/MR

Web guru. Amateur thinker. Unapologetic problem solver. Zombie expert. Hipster-friendly travel geek. Social mediaholic.