Winifred Blackman, on the other hand, had little to fight the skeptics. He did not begin his apprenticeship at Oxford until the age of 40, but then spent several months each year with Egyptian farmers for nearly two decades and had close family ties there. His research was also successful, but was never financially secure. After each season in the field, he feared for further promotion. A problem that – in contrast to male peers – was almost chronic for female anthropologists.

The fear of Czaplicka’s money may have cost him his life as well. In a hopeless state, he swallowed pills and died at the age of 36. Even the affluent Routledge could not count on her wealth, as it was given to her husband after the separation. These women scientists could not completely escape the narrow confines of their male dominated world. But was at least her research transcending all gender boundaries?

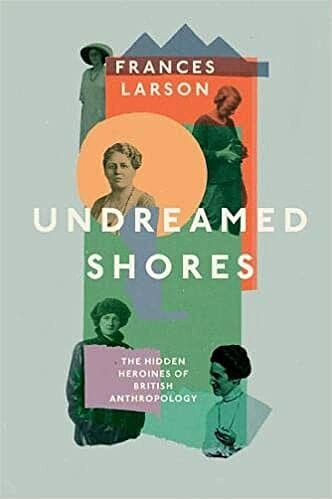

Some works have been lost, while others are still valuable today. Or at least it could be: as Larsen writes, the forerunners of the then new discipline are almost completely forgotten. Because anthropology not only established itself at the beginning of the last century, but changed rapidly from the ground up. While women were still doing important work, a new approach took hold. Instead of covering large areas in the distance, anthropologists must now focus long and hard on a single community.

However, this does not do justice to the early Oxford researchers, some of whom were strangers in their own countries and perhaps because of this they approached distant cultures with particular sensitivity. It is undeniable, for example, that questions about relationships, domestic issues, and childcare may have been closed to most male scientists. So it’s time to bring these attractive ladies into the limelight. Larsson’s brilliant book is in dire need of a German publisher – and a larger readership.

Web guru. Amateur thinker. Unapologetic problem solver. Zombie expert. Hipster-friendly travel geek. Social mediaholic.