When did bacteria acquire the ability to generate energy from light and release oxygen in the process? Depending on the dating method, the answer to this question will vary greatly. Using a combination of genome and fossil data, the researchers have now come to this conclusion: oxygen-producing cyanobacteria evolved between 3.4 and 2.7 billion years ago – at least 300 million years before oxygen increased in the atmosphere.

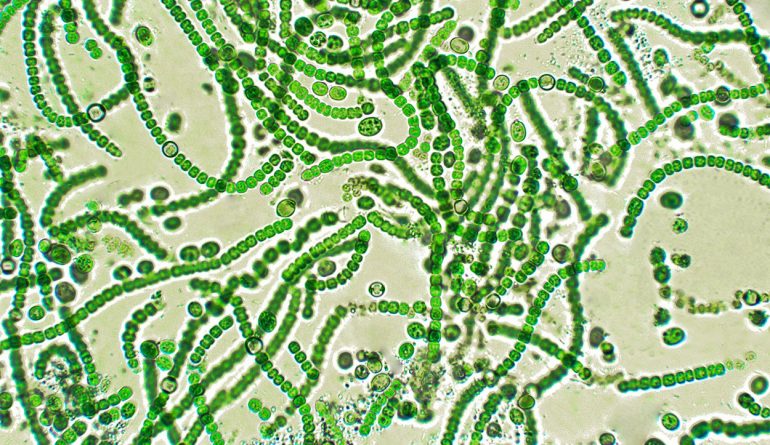

The development of photosynthesis laid the foundation for life as we know it today. At a time when oxygen was still toxic to most living things, cyanobacteria began to release this toxin as a product of their energy production from sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide. As a result, 2.4 billion years ago, the so-called Great Oxygen Disaster occurred: the oxygen content of the atmosphere increased massively, which not only caused the mass extinction of anaerobic bacteria that lived at the time, but also enabled the evolution of today. Oxygen based life. However, exactly when cyanobacteria evolved was not clear until now.

molecular clock complement

Previous dating was usually based on a method of creating a “molecular clock” based on mutation-related changes in the bacterial genome, which is estimated to have caused the different bacterial lines to diverge from each other. However, depending on the model used, these estimates fluctuate significantly, as without external reference points it is often not clear how quickly the changes occurred. A team led by Greg Fournier of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge has combined the molecular clock with another method: the researchers also analyzed what is known as horizontal gene transfer. These are rare cases in which a bacterium acquires genes from different species. This can happen, for example, when one cell eats another and in the process incorporates some of its genes into its genome.

In these cases it is clear that the group of organisms that can handle the gene must be evolutionarily smaller than the group from which the gene originated. The method therefore does not allow absolute information, but enables the relative age of different bacterial groups to be determined in comparison. Fournier and his colleagues took advantage of this. First they built various molecular clock models on the origin of cyanobacteria based on genome and fossil data. “In order to decide on an empirical basis which model best reflects reality, we then used relative age, which can be derived from horizontal gene transfer events,” explains the researchers.

slow onset of photosynthesis

The team found 34 clear cases of horizontal gene transfer in the genomes of thousands of bacterial species. The relative age dating obtained from this confirmed one of the six molecular clock models already established. According to this, the last common ancestor of all cyanobacteria living today arose about 2.7 billion years ago. According to the model, cyanobacteria diverged from other bacteria about 3.4 billion years ago. “Based on the genetic data known to date, it is still unclear when photosynthesis with oxygen occurred during this period, as related bacteria that lived in the transition period are either extinct or have yet to be discovered. Haven’t gone,” explain the researchers.

However, oxygen-producing bacteria did not emerge until 2.7 billion years ago – and thus at least 300 million years before the Great Oxygen Disaster. This supports theories that cyanobacteria quickly developed the ability to produce oxygen, but it took some time for oxygen to gain an effect in the environment. “In evolution, things always start small,” Fournier says. “Even if oxygen-producing photosynthesis was initially there — the most important and truly amazing evolutionary innovation on Earth — it took hundreds of millions of years to go.”

Growing impact 2.4 billion years ago

The finding fits with earlier evidence from rock analysis, according to which the elements were oxidized at least three billion years ago. One source of the oxygen needed for this could have been photosynthesis, whereby the oxygen was bound in the rock rather than enriched in the atmosphere. “Age estimates suggest that early cyanobacteria had little effect on the global environment,” the authors write. However, according to genetic analyses, cyanobacteria promoted diversification 2.4 billion years ago. “The most common and diverse groups of cyanobacteria appear to have spread at the time of the Great Oxygen Disaster,” the researchers say.

From their point of view, this indicates that the proliferation of cyanobacteria, among other factors, caused the great oxygen catastrophe – with all consequences for further life on Earth. The authors intend to use the horizontal gene transfer information-assisted dating method in the future to trace the origins of other species. “This work shows that molecular clocks that involve horizontal gene transfers (HGTs) can reliably determine the age of clusters throughout the tree of life, even for ancient microbes that left no fossil record. – something that was previously impossible,” Fournier says.

Quayle: Greg Fournier (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge) et al., Proceedings of the Royal Society B, DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2021.0675

Web guru. Amateur thinker. Unapologetic problem solver. Zombie expert. Hipster-friendly travel geek. Social mediaholic.