Two cancer-causing genes also control metabolism in the liver

The global obesity epidemic has increased the risk of liver fat accumulation, a precursor to liver inflammation and liver disease. However, a still puzzling paradox is the development of fatty liver in lean and normal weight individuals and in individuals who eat a healthy diet. Scientists know that two genes, RNF43 and ZNRF3 are mutated in liver cancer patients. However, their role in the development of liver cancer was previously unknown. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden now report that loss or mutation of these genes in non-obese mice fed a normal diet leads to lipid accumulation and inflammation in the liver. These genetic changes not only lead to an increased accumulation of fat, but also an increase in liver cells. In humans, these changes also increase the risk of NASH and fatty liver disease and shorten the life expectancy of patients. These findings may make it easier to identify those at risk and enable new therapeutic approaches and better treatment of the disease.

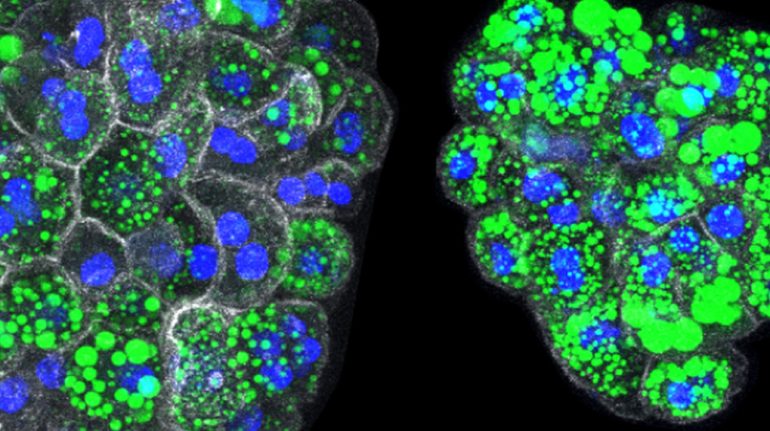

Organoids from liver cells of normal (left) and mutant (right) mice, with accumulation of lipids in green. When two genes (RNF43 and ZNRF3) are mutated, liver cells produce high levels of fat on their own, which also accumulate as large droplets inside each cell (nuclei in blue and white in white). recognizable by the surrounding cell membrane in colour).

© Belenguer et al. Nature Communications 2022 / MPI-CBG

The liver is our central metabolic organ, essential for detoxification and digestion. Chronic liver diseases such as cirrhosis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH, inflammatory liver) and liver cancer are on the rise worldwide, killing two million people each year. Therefore, it is more important than ever to understand the causes and underlying molecular mechanisms of liver disease in order to prevent, control and treat the growing patient population. Previous cancer genomic studies identified RNF43 and ZNRF3 as genes that are mutated in patients with colon and liver cancer. However, their involvement in liver disease is not known. Meritxel Hutch’s research group at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, with collaborators Gurdon Institute (Cambridge, UK) and on Cambridge University investigated the mechanisms by which alterations in these two genes may influence the development of liver diseases.

To get to the bottom of this question, the researchers worked with mice as an animal model, with data from patients, with human tissue and with so-called liver organoid cultures, which are tri-hepatocytes composed of liver-like hepatocytes. are dimensional cellular microstructures. in a bowl. German Bellenguer, first author of the study and postdoc in Meritxel Hutch’s group, explains: “With organoids, we were able to grow hepatocytes that only mutated in these genes, and we saw that the loss of these genes triggers a signal Regulates lipid metabolism. As a result, lipid metabolism is no longer under control and lipid builds up in the liver, which in turn leads to fatty liver. Furthermore, activating signals cause hepatocytes to multiply uncontrollably Together, both mechanisms promote the progression of fatty liver disease and cancer.”

less chance of survival

The scientists then compared the results of the experiments with patient data in publicly available datasets from the International Cancer Genome Consortium. They examined survival probabilities in patients with liver cancer when two genes were mutated and found that patients with these mutated genes tended to have fatty liver disease and a worse prognosis than liver cancer patients who had two. The genes are not mutated.

“Our results may help identify people with RNF43/ZNRF3 mutations who are at increased risk of developing fatty liver or liver cancer,” explains Meritxel Hutch. She adds: “With the alarming increase in fat and sugar consumption around the world, it may be important for therapeutic measures and management of the disease to identify individuals who are particularly vulnerable to it due to their genetic mutations. We will need further studies to further elucidate the role of two genes in human fatty liver disease, NASH, and human liver cancer, and to identify those therapeutics. for those who are more likely to develop the disease already naturally.”

Web guru. Amateur thinker. Unapologetic problem solver. Zombie expert. Hipster-friendly travel geek. Social mediaholic.