A newly discovered fossil in the Central Tablelands, northwest of Sydney, provides unique insight into the region’s prehistoric ecosystem. While today’s landscape is characterized by scrub, grass and desert areas, it was overgrown with rainforests about 15 million years ago. This is suggested by the many well-preserved fossils of plants, insects, spiders and fish. However, pollen already shows the first signs that dehydration was beginning at that time.

During the Miocene, about 23 to 5 million years ago, the landscape and ecosystem in Australia changed dramatically. If the continent was still fertile and species-rich at the beginning of the era, about 14 million years ago climate change resulted in the mass extinction of many animals and plants. Australia dried up and former rainforests gave way to the scrub, grassy and desert landscapes that characterize large parts of Australia to this day. A team led by Matthew McCurry from the Australian Museum in Sydney writes, “The paucity of well-preserved fossils has so far made it difficult to understand the structure of Australian ecosystems before they dried up.”

Rainforest in transition of drought

It was not until 2017 that a unique deposit of well-preserved fossils from the Miocene was discovered, the McGrath Flats, named after its discoverer. The site is located near the city of Gulgong in central New South Wales, approximately 250 kilometers northwest of Sydney. McCurry and his team have been excavating fossils at McGrath Flat for three years and have now published the first comprehensive analysis. “Until now, it has been difficult to say what these ancient ecosystems looked like, but the degree of preservation of this new fossil site means that even small, delicate creatures such as insects have become well-preserved fossils,” says McCurry. .

The fossils were between eleven and 16 million years old – the exact same stage in which climate change took place. “The fossils we found suggest that the region was once a temperate, moderately humid rainforest and that life was rich and abundant in the Central Tablelands,” McCurry said. However, signs of the onset of drought are already visible: “The pollen we found in sediments suggests that the area around more humid rainforests may have drier habitats, indicating a change in drier conditions.” ” McCurry says. In addition, the researchers discovered the remains of hard-leaved plants, which are also typical of arid regions.

Extraordinarily Preserved Fossils

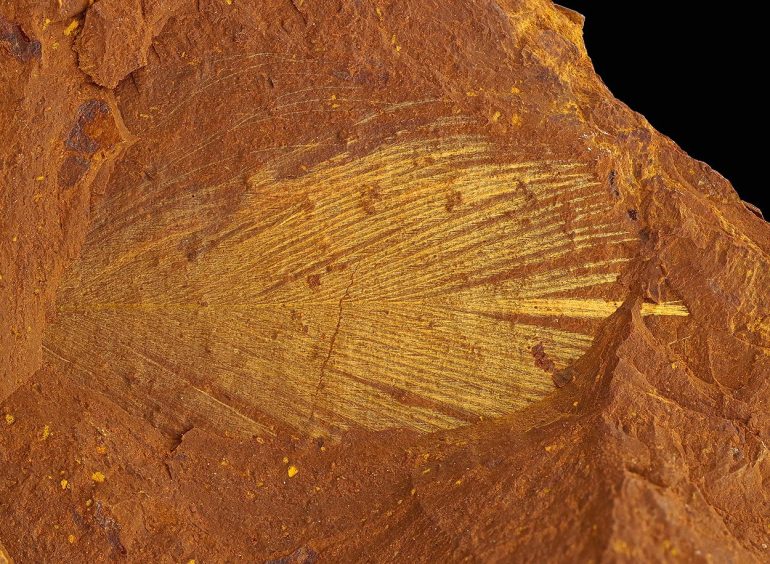

With the help of various microscopic techniques, including scanning electron microscopy, the researchers were able to image the tiny structures of the fossils. In this way, they got a glimpse of how species interact with each other. “For example, we evaluated the stomach contents of fish so that we could find out what they ate,” explains McCurry’s colleague Michael Freese. Among other things, they found worm larvae and even the remains of a dragonfly’s fin in the stomach of the fish. “We also found examples of pollen that are preserved on the bodies of insects so that we can determine which species pollinated which plants,” says Freese.

The fossils were preserved in an iron rock called goethite, which is generally not known as a source of well-preserved fossils. But from the researchers’ point of view, only the process that turns the organisms into fossils may explain why they were so well preserved. According to this, the fossils probably formed in a so-called billabong, a body of water that often formed from a branch of a river and, depending on the amount of precipitation, sometimes dried up. “Our analysis shows that fossils are formed when iron groundwater flows into a billabong. The iron minerals included settler organisms that lived or fell in the water,” explains McCurry.

Past and future in a warm world

According to the researchers, the fossils provide an earlier unique insight into Australia’s ecological past and may also provide a glimpse into the future. “Plant fossils from McGrath’s Flat give us a glimpse into the flora and ecosystems of a warmer world, a world we may see in the future,” says co-author David Cantrill from the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, Australia. “The preservation of plant fossils is unique and provides important insight into the period for which there are few fossils in Australia.”

Quayle: Matthew McCurry (Australian Museum Research Institute, Sydney) et al., Science Advances, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abm1406

Web guru. Amateur thinker. Unapologetic problem solver. Zombie expert. Hipster-friendly travel geek. Social mediaholic.