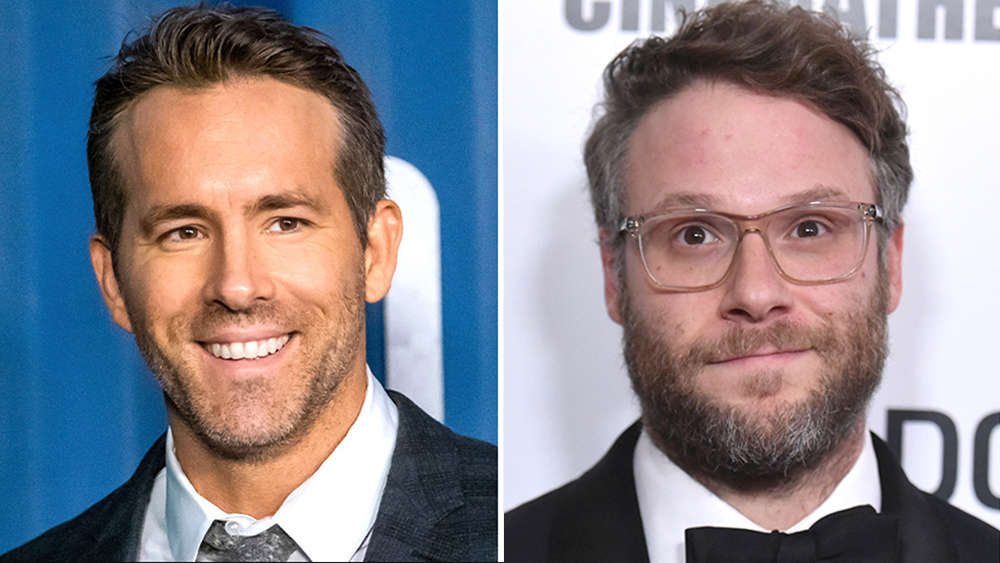

A woman in Surrey, B.C., and man in Blaine, Wash., speak to each another across the Canada-U.S. border, which is marked by a ditch, at Peace Arch Historical State Park, on Dec. 19, 2020.

DARRYL DYCK/The Globe and Mail

To some, the park at the British Columbia-Washington state border has served as a sliver of normalcy in what has been a thoroughly abnormal year. Amid COVID-19 shutdowns, travel restrictions and orders not to socialize with others, Canadians and Americans have been able to wander into the picturesque park to meet up.

To Rick Robinson, who lives across the street in Surrey, B.C., it’s been nothing but a pain.

“Realistically, you can’t be doing this,” said Mr. Robinson, a fast-talking 72-year-old with little patience for nonsense. “They’re sitting at the aluminum tables, and nobody’s coming along and washing those tables after people leave. The kids are hanging on the playground [equipment] and sucking on their fingers and all kinds of stuff, on the swings. People are hugging and kissing and, of course, making love in those tents.”

The Canadian half of the park at the Peace Arch Border Crossing has been closed since June 18, but the 19-acre plot on the U.S. side has remained open to visitors from both sides. Canadians can walk into Peace Arch Historical State Park without declaring themselves to border agents as long as they return to their country of origin.

B.C. RCMP, who have increased their presence in the area, say Canadians who visit the U.S. side of the park “must expect to adhere to any current federal and or provincial Health orders and any necessary quarantine/isolation periods that are in place.” However, visitors seem unaware of that expectation, and officers along the border only check the IDs of returning visitors to ensure they are Canadian.

The result is an area that’s bustling with residents of both countries like never before. There are cookouts and weddings and, to Mr. Robinson’s chagrin, enthusiastic couples celebrating their reunions under the flimsy cover of tents. Border agents and park rangers can rattle off a long list of visitors’ home states, and a scan of the licence plates in the parking lot seems to confirm it: Arizona, California, Wisconsin, New Jersey, Texas.

A recent sunny day at the park looked like something from prepandemic times. Children chased one another around a swing set as parents, bundled in winter jackets, looked on from their circles of camping chairs. Friends and families towed wagons of food and condiments to picnic tables, where they barbecued hot dogs and burgers. The eastern side of the park was dotted with about 50 tents.

Sandwich boards reminded visitors of four rules: Wear a mask while walking through the park; stay six feet from others; groups must have no more than five people; and no tents of any kind. Every rule is broken at any given time.

A man kisses a woman after a wedding ceremony in a tent with Canadian and U.S. attendees at Peace Arch Historical State Park in Blaine, Wash., across the Canada-U.S. border from Surrey, B.C.

DARRYL DYCK/The Globe and Mail

Asked how he knows there’s funny business going on in the tents, Mr. Robinson said it’s obvious. “Some of them are moving. What do you think they have a tent for? They’re not playing cards in there.”

Among recent visitors were Australians Rebecca Race and Nathan Shaw, who had been travelling across North America in an RV. The pair arrived in B.C. – where Mr. Shaw’s sister, Cara Shaw, and her partner, Luke Speed, are permanent residents – in February and crossed the border into the United States in March. The border was closed to non-essential travel four days later, preventing Ms. Race and Mr. Shaw from driving back into B.C. as planned.

The foursome reunited once in September, with the two couples sitting on opposite sides of a ditch that separates B.C. from Washington State.

“We didn’t realize then that this was a thing,” Ms. Race said of the park, where the four sat toasting hot dog buns on a portable barbecue this month. “We thought this time we would try this – and it’s so easy.”

“It’s a little surreal being in Vancouver, in lockdown – you know, pretty much in lockdown – and then we come here and it’s like, ‘Oh, there’s a park. And there are people,’” Mr. Speed said.

He added that it was during the “ditch party” that RCMP officers told them about what was happening in the tents.

“If the tent’s a-rockin’, don’t come a-knockin’,” Ms. Race said.

Keith Kings lives in Blaine, Wash., which would normally be a 20-minute drive from his girlfriend’s house in White Rock, B.C. During the pandemic, they’ve tried to meet at Peace Arch once a week, sitting in camping chairs on the grass when it’s warm and in a tent with a heater when it’s not. A cancelled trip to Las Vegas became a Vegas-themed games day in the park.

The pair met with two other friends from B.C. at Peace Arch this month.

“I call it the Peace and Love park for a reason, because it’s good for people to have this feeling again,” Mr. Kings said. “Some of the neighbours here are putting up a big stink about it … but people are getting to see their grandkids, to see their families.”

They, too, are well aware of the activity in the tents.

“You can hear it,” said Mr. Kings’s friend Steve Hartle. “It’s like a festival without the music.”

A tree is decorated with Christmas decorations as people meet in a tent at Peace Arch Historical State Park in Blaine, Wash.

DARRYL DYCK/The Globe and Mail

Bibiana Demcak and her husband, a pair of travelling magicians from Richmond, heard about what was happening at the park and went down to see it for themselves.

“It is a big concern,” Ms. Demcak said as her partner looked on disapprovingly. “The virus is spiking. It’s Christmas time, yes, people want to get together, we are human beings, with strong relationships – but it takes so little to bring grandma and grandpa to the grave. Do you want to celebrate your Christmas at a funeral home?”

Rick Blank has been a Washington State park ranger for 46 years, the past two at Peace Arch Historical State Park, where he’s the manager. He doesn’t have official visitor counts for this year yet but can illustrate the surge in a few ways.

In any normal week before the pandemic, he would collect about three cubic yards of garbage, he said; this summer, it reached 43 a week. The Sunday of the Labour Day weekend would usually draw about 300 people to the park; this year it saw almost 2,000. And the 218-stall parking lot that was full maybe once or twice in all of 2019? It was full every weekend this summer and some weekends into the fall as well, he said.

(Mr. Robinson said there are finally No Parking signs up on his residential street, “but there’s still idiots that park there sometimes.”)

Mr. Blank, who locals call Ranger Rick, estimates the park played host to 20 to 25 weddings a week at the height of summer.

“It’s just really busy,” he said. “It makes me happy because this has been a little jewel here for folks to enjoy, but it has never been used as heavily as it is right now.”

He’s aware that some people are flouting the rules. But he governs with a carrot rather than a stick, issuing moral pleas rather than threats and penalties: “Hey, the governor’s mandate is groups no bigger than five. And could you please wear your masks?”

Rangers have the authority to issue citations and ban people from the park for a day, a month or even a year, “but no one’s been that bad yet,” he said.

“The joy I have is that people are using the park and recognizing what a special place and opportunity this is,” Mr. Blank said. “Ninety-nine per cent of all the people are using it wisely and trying to follow the rules and do the best they can. And they don’t want to lose this opportunity.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Devoted web advocate. Bacon scholar. Internet lover. Passionate twitteraholic. Unable to type with boxing gloves on. Lifelong beer fanatic.