Beijing can only smile at Europe’s “Anti-Silk Road”

EU project has so far found little to oppose China’s New Silk Road

Source: Getty Images, AP; Montage: Infographic World

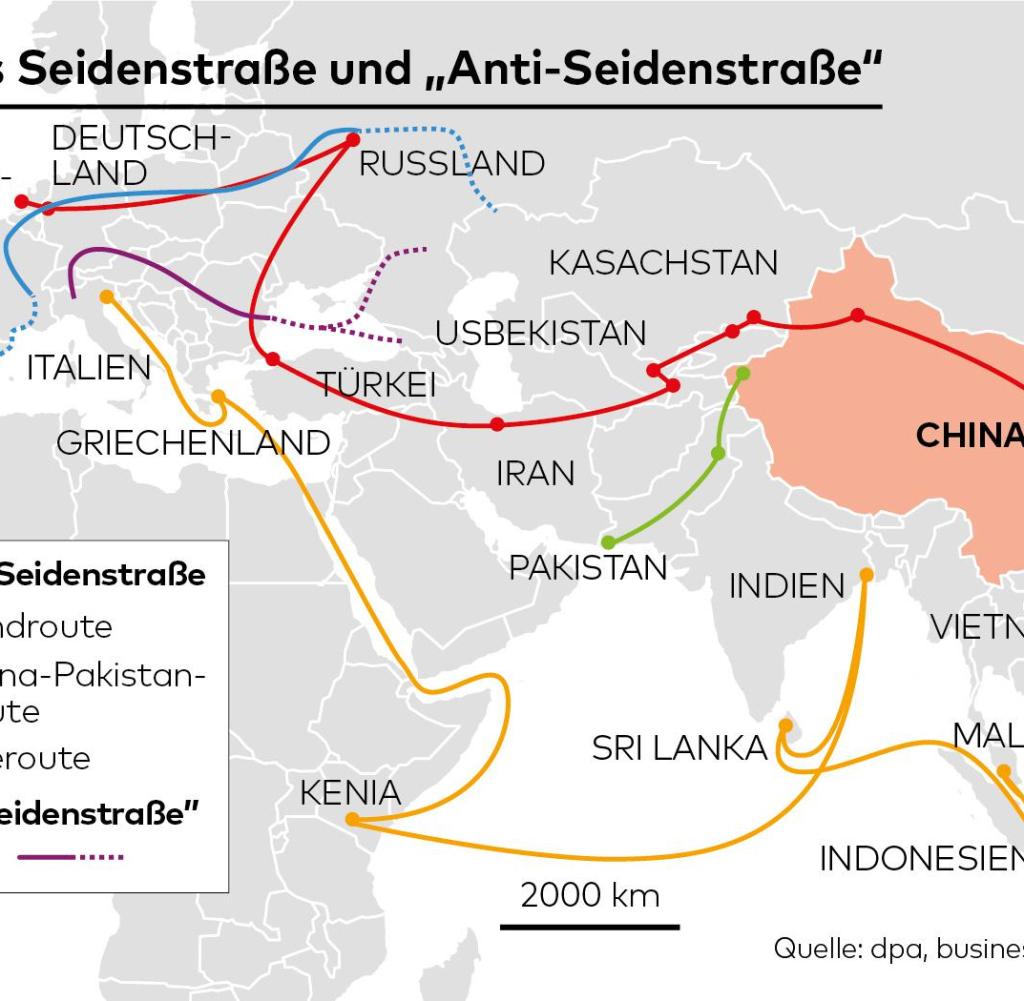

With the mega-project “New Silk Road”, China is steadily expanding its geopolitical influence in Europe as well. After years of hesitation, the foreign ministers of EU member states are now reiterating their counter-initiative. But the result is little more than a theory.

IIt all happened very quickly. The foreign ministers of EU member states began their deliberations in Brussels at around 9:30 a.m. on Monday. Less than an hour later, with admiration, he adopted a document for Europe with great vision and immense consequences – at least if good words were to be followed by deeds.

The objective is a “Globally Network Europe”. Simply put: The EU seeks to counter China’s project of the New Silk Road (Belt and Road) with its so-called connectivity strategy so that Beijing is no longer left alone in the battle for new markets and political influence. It is about the geopolitics of the EU, but also about a silent revolution in the European economy, with future global partners engaging more closely than ever. Only: Unlike Beijing, Brussels’ strategy has so far been mainly a paper tiger, progress is barely visible – and an entire region of the world has been explicitly excluded from the plans.

Source: Infographic Die Welt

Cooperation with China’s Silk Road project is not planned. However, Europeans want to coordinate their global infrastructure policy more closely with Washington within the framework of the G-7 states. However, it is surprising that the seven-page document does not mention Africa as an important connectivity partner. It only emphasizes that EU countries should develop “connectivity partnerships” with “like-minded countries and regions” such as India and Japan, especially in Asia.

But what is it exactly? Simply put: with the new connectivity strategy, the EU wants to network with other continents over thousands of kilometres. This is mainly due to new transport connections by air, land and sea. It also includes digital networks ranging from cellular networks to landlines, from cable to satellites. Energy networks and lines for electricity or natural gas are also essential. In Asia alone, investment in infrastructure requires 1.3 trillion euros annually.

Its aim is to exchange goods, services and information as quickly and cheaply as possible, ultimately benefiting all parties. It is about profit in optimizing the international division of labour, about new sales and production markets, declining transportation costs and thus ultimately prosperity. Although Europeans do not talk about this openly, for the EU it is also about exercising political influence in partner countries – not least to strive for Beijing’s power and help “a worldwide expansion of sinocentric structures”. for those who are not in our interest” (Foreign Office).

impact through strategic investment

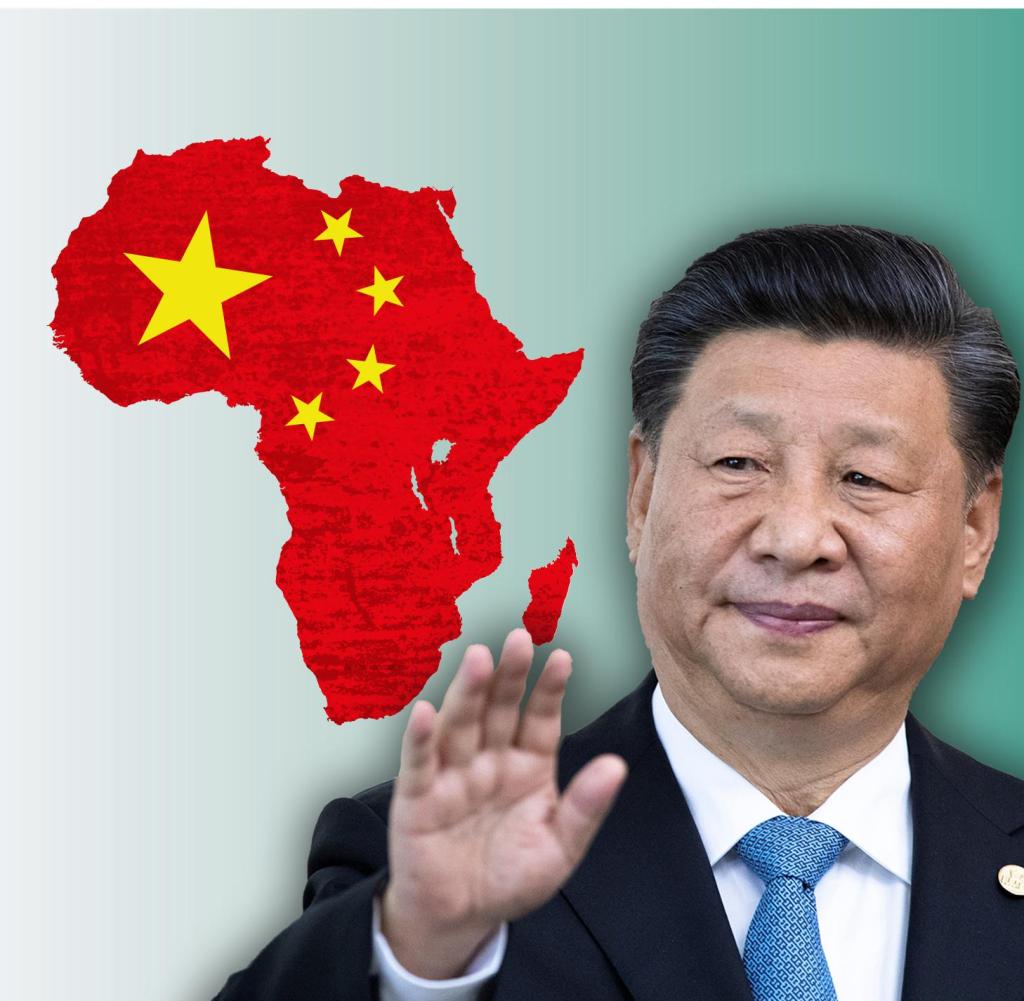

This is a huge, very expensive effort that the Europeans are planning. He has been challenged by Beijing since 2013. With his geopolitical master plan New Silk Road, Chinese President Xi Jinping is seeking to establish the Middle Kingdom as the world’s strongest economic power through billions of infrastructure investments and international debt.

At the same time, Beijing seeks to expand its influence on politics, finance and research globally. Paul J. Kohlenberg and Nadine Godehardt describe exactly how this works in an article for the Science and Politics Foundation (SWP): “The connectivity policy with Chinese features works primarily with the concept of ‘strategic docking’. It addresses the way you connect. Only as an active part is it possible to pre-set the agenda for newly created connections and to determine points of contact with other actors and states.”

Beijing has been successful in making strategic investments not only in Asia or Africa, but also in Greece, Italy, Hungary and the Western Balkans.

Europeans want the same now. But Brussels’ counter-attack runs the risk of losing itself and losing itself to the EU’s bureaucratic swarm. There is little hope that the European plans will ever succeed. In early 2018, EU countries presented a concept for a connectivity strategy between Europe and Asia. Still, Africa played no role. The then EU foreign affairs representative, Federica Mogherini, declared: “This is the European way of tackling challenges and seizing opportunities so that the peoples of Europe and Asia benefit.”

But nothing happened in the last three years. EU MP Reinhard Butikofer (Greens) says the 2018 strategy has been a “car without wheels”: “Member states have hardly paid attention to it. Neither does the Commission have many directorates general. President Ursula von der Leyen Never lost a single sentence on connectivity strategy.” Brussels slept through the rise of China for years.

Almost word-for-word as it was in 2018, the EU foreign ministers’ document now states that connectivity must be “sustainable, comprehensive and rules-based”. It is therefore important to take a cooperative approach, not strive for dominance in Beijing. The Brussels bureaucracy is now doing its job: the EU Commission should submit some suitable projects by the “latest spring 2022”. The authority has also been directed to prepare a new document for the “Common Global Connectivity Strategy”. Until then, China will keep moving towards its goals – with big, fast steps.

Introvert. Proud beer specialist. Coffee geek. Typical thinker. Pop culture trailblazer. Music practitioner. Explorer.