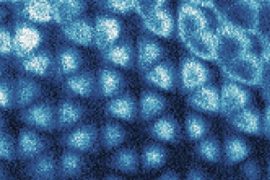

monkeypox virus under electron microscope

Photo: DPA/RKI/Freya Kaulbers

Readers over the age of 50 will often find an older, more or less elliptical mark on one of their upper arms. It is the visible sign of vaccination against (human) smallpox, the once dangerous plague that may have appeared in ancient Egypt. However, thanks to vaccination campaigns around the world, smallpox caused by the variola virus could be defeated in the 1970s. In 1980, the World Health Organization announced that chicken pox To end the world. Unlike most other smallpox viruses, variola circulates only between humans. If and when the variola virus originally spread from the animal kingdom to humans and adapted to this new host is no longer clear, more than 3000 years later. But there is a possibility of such infection. Because practically all known orthopoxviruses have other mammals as natural reservoirs, often rodents, which themselves are not sick. And the very useful vaccine itself is based on a pathogen that also affects animals. Contrary to the name vaccinia virus (from the Latin vaccine for cow), vaccinia virus is probably more closely related to the horsepox virus than to smallpox. Fortunately, familial ties to the variola virus have not been associated with severe disease by comparison. The vaccinia virus was most recently used in the smallpox vaccine and is still weak in the laboratory in storage today. Modern vaccines use the so-called modified Vaccinia Ankara virus (MVA), which is no longer able to reproduce in mammals.

Even if the vaccination is at best 40 years old, it probably still provides a fairly good level of protection. “We have known since the time of the global vaccination campaign to eradicate human smallpox that a single vaccination with a breeding live vaccine was sufficient to have a very long-term protective effect,” says Gerd Sutter, a virologist and veterinarian at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. ” , Even decades later, specific memory cells of stimulated immune response to prove. So Sutter believes that vaccinated people have at least partial protection from monkeypox. However, it is difficult to assess the remaining protective effect, as there is not enough data on the epidemiology of monkeypox, which occurs relatively rarely.

old mostly preserved

However, only the Old Germans mentioned above would receive this protection. Because compulsory vaccination against smallpox, which was in force since 1874, ended in 1976 in the old FRG, in 1981 in Austria and in 1982 in the GDR. Most babies born later no longer have this vaccination protection. Until now, this seemed irrelevant, as it was first diagnosed in humans in 1970. monkey pox, which is probably known as squirrel pox after its potential host, occurs very rarely. They are also rarely transmitted from person to person, but mostly after very close contact with infected animals. Furthermore, the course of the disease is usually relatively harmless. However, the current unusual accumulation of monkeypox cases in Western countries is a cause for concern, as many of the more than 300 confirmed cases worldwide contracted the infection either on trips to West Africa or through contact with known animals. not done.

The head of the Permanent Immunization Commission (Stico), Thomas Mertens, considers preventive vaccination of at-risk groups – such as those who have weakened immune systems – to be useful against monkeypox in certain circumstances. “We’re currently thinking about that,” Mertens told the “Rheinish Post.” However, the older smallpox vaccine would not be suitable for people with immune deficiencies because it contains viruses that can reproduce. According to estimates by Herwig Kolarits, a Viennese specialist in vaccination and travel medicine, about a quarter of the population will no longer be vaccinated due to contraindications. Modern vaccines are not expected to cause any side effects. The MVA vaccine Imvanex from the German-Danish company Bavarian Nordic, which has been approved in the European Union for adults against smallpox since 2013, has also been approved against monkeypox in the United States. According to the UK Health Protection Agency, British health authorities have recently given more than 1,000 doses of it to the contacts of people infected with monkeypox. Epidemiologist Gerard Krauss of the Helmholtz Center for Infection Research in Braunschweig says that these vaccinations can currently only be done on a case-by-case basis for special circumstances.

no adaptations for humans

According to virologist Thomas Meittenleiter, the current spread of the monkeypox virus probably has nothing to do with humans’ better adaptation to the new host. But – according to the head of the Friedrich Löffler Institute responsible for animal diseases for the news channel N-TV – the longer a pathogen hangs around in a new population, the more likely it is that random genetic changes could lead to a disease. Customization. After all, the FLI does not currently expect native animal species to become reservoir hosts. “It may be possible that a pet, like a cat, is infected by direct contact with an affected individual, but at present it seems unlikely that a chain of infection would actually begin.”

In general, however, the number of infectious diseases transmitted by animals has increased in recent decades. There is an assumption that the Munich virologist Sutter confirms. “We’ve seen it for 20 years, starting with the sudden conquest of North America by West Nile fever in 1999: planes, mosquitoes, arrivals in New York—enough for it to spread across the North American continent in just a few years.’ The reasons are complex. On the one hand, people are increasingly entering areas they weren’t before. This means they come into contact with animals more often and open up a new host system for their pathogens. Also climate change change, which is bringing insects that transmit pathogens to other parts of the world as well as attitude and animal consumption Sutter’s perspective plays a role. In addition, there is a globalized travel activityWhich can carry a pathogen to half the world in two days.

A joint research project by the Robert Koch Institute and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology showed years ago that zoonos are not a one-way street. It is not just animal disease that spreads to humans, it also happens on the other side. According to Fabian Lendertz, founding director of the Helmholtz Institute for One Health in Greifswald, all respiratory diseases in the great apes observed in the 2008 study were caused by viruses that spread from humans to animals.

Web guru. Amateur thinker. Unapologetic problem solver. Zombie expert. Hipster-friendly travel geek. Social mediaholic.